There is a large, unidentifiable animal carcass floating downstream towards me. I watch it as I walk along the flimsy-feeling metal pedestrian bridge that crosses the river in this slum outside of Nairobi. The carcass is being carried along in liquid that doesn’t even look like water. The only place I’ve ever seen water that looks like this is in the various slums of Nairobi. It’s black. It’s gray. It’s inky and oily looking. It’s not translucent. And it’s not just mud.

Welcome to Mathare.

It’s the second largest slum in Kenya, with about 600,000 people crammed in an area only .2 by 1.2 miles in area, depending on who you ask and where you define the borders. It’s crowded. Crowded with people, with electrical wires, with tin shanties and rusted roofs, with clothes hanging from laundry lines, with garbage, and with sewage.

There’s so much trash and filth. Everywhere. Depending on how the wind blows in the slum, the pungent stench is overpowering. At least if you breathe through your mouth you don’t have to smell it. Snaking insidiously through the slum, open trenches with sewage running through them and trickling along the streets assure me there’s no way I’m walking into Mathare Valley without human and animal feces and all manner of filth coming out with me, at least on my feet, if not more.

There’s so much trash and filth. Everywhere. Depending on how the wind blows in the slum, the pungent stench is overpowering. At least if you breathe through your mouth you don’t have to smell it. Snaking insidiously through the slum, open trenches with sewage running through them and trickling along the streets assure me there’s no way I’m walking into Mathare Valley without human and animal feces and all manner of filth coming out with me, at least on my feet, if not more.

From the bridge I can see a “still” or “brewery” of sorts on one side of the riverbank where they make an “illicit brew” that I hear people refer to countless times. It seems to be the culprit of many problems in the slum.

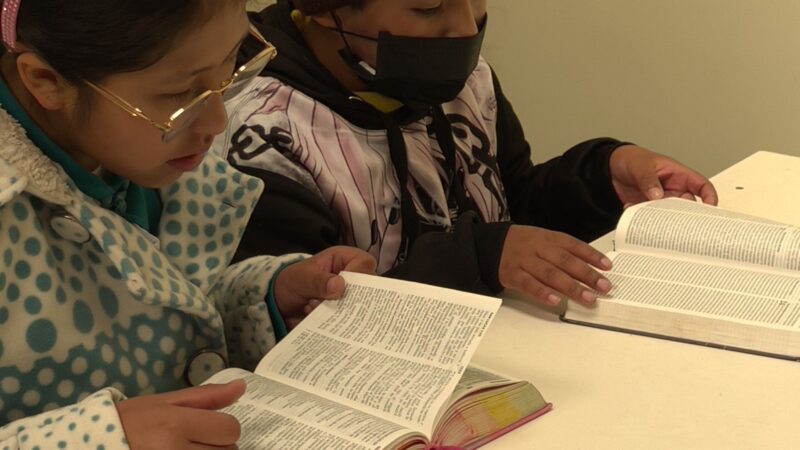

But there is exactly where I want to be right now. Because amidst all of this, I’m told that Mathare is actually getting better. Bright Hope and its church partner, Mathare Community Outreach, are working here, persevering day in and day out, to make a difference, one life at a time. That’s grown and grown, and now, also crowded in this slum and another nearby one, are about 1,200 children receiving an education and two meals a day at our partner schools…parents in micro-savings groups that are enabling them to pay school fees and build homes…and young adults who have received scholarships and whose lives—and therefore their children’s lives and their grandchildren’s lives—are now on a different trajectory, full of vision.

This is progress. Changing one life at a time, which changes one family at a time, starts to have a ripple effect for generations—and in the community. As much as we’d like to snap our fingers and overhaul the infrastructure for half a million people living in this kind of poverty, we just don’t have what it would take to do that. So, while we hope and pray for major change to come, we press on doing all that we can to help “the one.”

But while I look for the beauty in the middle of the hard and the ugly, I need you to understand, to the best of my ability, just how hard and ugly it can be. Why? Because Mathare Valley is a main character in every story we tell you from this place.

I can tell you that 13-year-old Pamela wants to be a biomedical engineer when she grows up, and that’s great, but her dreams and her fortitude will mean oh so much more when you know that she lives in a small, dark home in the slum with no running water or plumbing. They have to go fetch and carry back every single drop of water they use in their home.

I can tell you that 13-year-old Pamela wants to be a biomedical engineer when she grows up, and that’s great, but her dreams and her fortitude will mean oh so much more when you know that she lives in a small, dark home in the slum with no running water or plumbing. They have to go fetch and carry back every single drop of water they use in their home.

Pamela’s mother died when she was a baby, and she and her four siblings have been raised by their aunt. Pamela struggles with a chronic illness, does much of the cooking for the family…and plays basketball. I walked with her from her home to her school, and I watched her go to her desk—it’s so crowded and they’re so tightly packed in the classroom that the only way she can get to her seat is to crawl over the desk behind hers, step onto the seat, and scoot herself down into it.*

Now, if you had all those physical and emotional hurdles to overcome, and those were the conditions you had to go to school in, would you still dream of becoming a biomedical engineer?

I don’t think I would’ve.

And that’s why it’s so important to me that you understand the antagonist—sometimes hidden, sometimes not so hidden—in these stories of courage and hope.

Welcome to the valley. And hats off to girls like you, Pamela.

*There’s much more of Pamela’s story to share with you, which we’ll do at a later time.